“Art has always been closer to magic than logic, and this was more magical than most…or maybe we just didn’t give a fuck what people thought.” - Sylvain Sylvain, guitar player, New York Dolls.

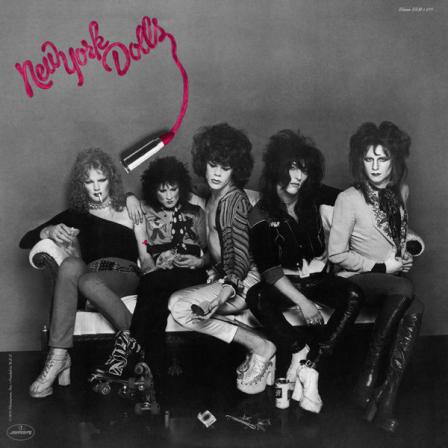

New York Dolls debut album, 1973. Left to right: Arthur Kane, Sylvain Sylvain, David Johansen, Johnny Thunders, Jerry Nolan.

The fun had gone out of the world by 1971 and the airwaves mottled with the sound of Cat Stevens’ “Peace Train” plodding through John Denver’s “Country Roads.” Nixon was still in, the Vietnam War still on and the false promises of a hippie utopia had finally collapsed under a rubble of reality that came from places like Altamont, and Kent State. And just like the world, the fun had gone out of rock and roll too, when a group of young men from the outer boroughs of New York City bonded on a journey to bring it back.

“The city was rotting from the inside; the bright lights of Broadway past dimmed and darkened…dangers in every neighborhood…garbage rotted on the streets…drug use was epidemic, the murder rate was soaring,” writes Syl Sylvain, in his memoir, “There’s No Bones in Ice Cream.”

“Then the New York Dolls arrived, plying their trade in those same bowel-like recesses, but doing so brighter than a thousand suns, a riot of sound and vision.”

You could make the convincing argument that a world in which the New York Dolls never existed would be a pretty drab place, musically, creatively, and - because inspiration works in generational ways that forever alter the world - in a variety of ways that can’t be measured. All this they achieved in the space of just over three-and-a-half years, during which they released two albums and performed (give or take) 300 gigs, bridging a void between the death of the Velvets and the birth of CBGB’s. Ultimately, they inspired a scene that spread across both sides of the Atlantic - the ramifications of which are felt to this day.

Sylvain Mizrahi was born on Valentine’s Day 1951 in Cairo, Egypt to a family of Egyptian Jews, whose first language was French. His was a stable childhood suddenly caught in a whirlwind one summer day, when at the age of five, Syl watched the cops burst into the family home and take his father away. The reason: a new political regime came into power and forbade Jews from working in government-controlled professions. After 25 years of service at a bank, his dad was out of a job and the family of five out of a home. Their migratory path of escape would zag through France and eventually deliver them to New York City.

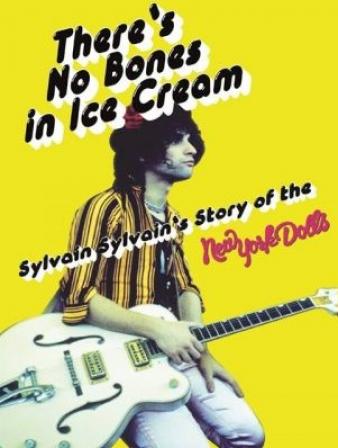

This is where Sylvain’s story begins, amiably assisted by prolific music journalist Dave Thompson, in the memoir: “There’s No Bones in Ice Cream: Sylvain Sylvain’s Story of the New York Dolls.” The 245-page book, published by Omnibus Press, provides a welcome addition of words related to the Dolls’ history, alongside Arthur Kane’s posthumously published memoir – “I, Doll,” in 2009, Nina Antonia’s “Johnny Thunders…In Cold Blood” and “The New York Dolls - Too Much Too Soon,” and Curt Weiss’ recently published bio of fellow beat-keeper Jerry Nolan, titled “Stranded in The Jungle: Jerry Nolan's Wild Ride.”

“There’s No Bones In Ice Cream: Sylvain’s Sylvain’s Story of the New York Dolls,” – by Sylvain Sylvain and Dave Thompson.

Shortly after the Beatles landed in America, the Mizrahi Family settled down in a one-bedroom apartment on the seventh floor of a building on Hillside Avenue in Jamaica, Queens. Syl attended classes at public school, met girls at the social dances – “all of them wearing their tight pink mohair sweaters, looking like Mary Tyler Moore, Ann-Margret and Mary Weiss.”

When a new family trade was required, tailoring became the chosen profession. Young Syl picked up lessons cutting, tracing and sewing and took needle-and-thread to his clothes to start creating “a look.” It is a trade that would later serve him and his bandmates well. “I never cared about what was fashionable, I cared about what I wanted to wear, and if I couldn’t buy it anywhere else, I’d make it. I would take the same approach with me into music. Into the New York Dolls,” he writes.

Sylvain’s New York childhood was filled with comic books, movies and learning to play guitar in feeding his growing passion for rock ‘n’ roll. He hung out at the bowling alley and spent summer days at Brighton Beach, or Coney Island, with the transistor knob tuned to WMCA Good Guys on the radio dial. “Later on, in the New York Dolls, all the little ‘ooohs’ and ‘aaahs’ that were so much of our signature sound, I took them all straight from the beach when I was 11 or 12 years old.”

His small body frame made him a target of bullying during his junior high school, but even here there was a silver lining. One schoolyard fight involved a just-as-reluctant classmate from Bogota, Columbia, whose family, like Sylvain’s, had migrated to Queens, N.Y. in the early 1960s. The boys put on a fake, yet convincing show that mollified the crowd of students gathered to watch the spectacle. “Then we went home with our arms together and we became best friends. And that is how I met Billy Murcia, the drummer with the original New York Dolls,” Sylvain says. The boys’ friendship blossomed into a brotherhood and led to late afternoon musical jam sessions at Billy’s family’s home. Nights were occupied by hopping the subway train to Manhattan to hang out in Greenwich Village where the late ‘60s music scene was in full abandon. During their high school years, they began expanding their circle of friends.

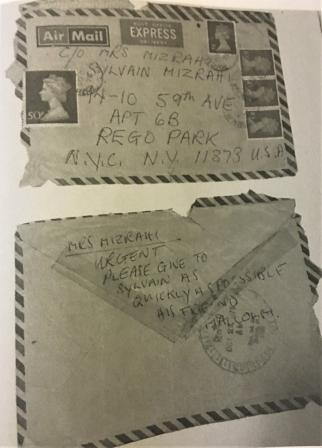

“Urgent” letter from Malcolm McLaren to Syl, image from the book, “There’s No Bones In Ice Cream.”

“I started to notice a really cool-looking cat in the lunchroom at school or in the hallways between classes,” Syl recalls of their fellow Queens classmate Johnny Genzale, who a few years later would adopt the name Johnny Thunders. “I went up and asked him straight: ‘Hey man, me and Billy have got a band. Do you wanna join?’”

With his school days behind him, Sylvain took a job at a clothing shop located opposite a business whose neon sign “destined to haunt my daydreams for years to come. It was called the New York Doll Hospital…wouldn’t that be a great name for a band?”

By 1971, Arthur Kane and George Fedorick (aka Rick Rivets) came into the musical fold, renting a room at Billy’s mother’s Queens apartment building, jamming in the basement with Murcia, and at various times with Sylvain and Thunders, on a repertoire of Stooges, Ventures, and Chuck Berry tunes. By early 1972, David Johansen was brought in to sing and Sylvain became a permanent member, replacing Rivets.

“We were five friends from the boroughs who united over music, movies, art and lust, and wore the clothes that shouted out that bond,” Syl writes. Their earliest days produced a string or original creations - “Bad Girl,” “Vietnamese Baby,” Personality Crisis, Subway Train, and “Looking for a Kiss,” among them. There was a heavy blues influence in the music, albeit altered by the band’s simple mantra: “We T.Rex’ed the shit out of everything,” Syl says. “That became one of the blueprints for a lot of our early songs.”

With “No Bones In Ice Cream,” Sylvain documents the band’s journey from their earliest showcase gigs in 1972 to their spring of 1975 apocalypse. Along the way they were eyed by Bowie, scouted by the Stones and Richard Branson, and both highly praised and mercilessly reviled by fans and critics alike. The book trips through hallowed halls like Max’s Kansas City, documents gigs with the likes of Mott The Hoople, Aerosmith, and Kiss, and recalls the ominous night that the Mercer Arts Center collapsed.

“The big day arrived. Aug. 3, 1973. The New York Dolls (with Mott the Hoople) at the Felt Forum. It was the biggest show we had ever played in America, and how did it begin? The Mercer collapsed…It was five o’clock – the height of the rush hour – and it took just seconds for all eight floors to be reduced to rubble…was it an omen? The Mercer had made us what we were. What would we become with it gone?”

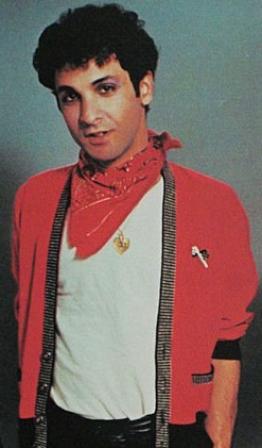

Sylvain selfie, from Sylvain Facebook page, August 2018.

There are memorable gigs: performing with Rod Stewart and Faces in front of 12,000 people at Wembley Pool, playing a Valentine’s Day 1974 gig at the Academy of Music in New York; dressing in drag (all except Thunders) at a Club 82 Easter Party in 1974. “When you take the stage, no matter who you’re sharing it with, you’ve got to promise to die. To detonate. To fly as high as you can and then, like the Fourth of July, explode like a sky full of fireworks,” Syl writes. “Give them a killer show every night. Lead, follow, or get out of the way; it’s a rich man’s war, but a poor boy’s fight.”

There are some not-so-great-events, equally memorable: Johansen was arrested by the vice squad while onstage in Memphis and charged with inciting a riot; the entire group was banned at the then-new Bottom Line club after the Dolls were blamed (falsely, claims Syl) for phoning in a bomb threat that cleared the venue. There is also a brief passage regarding the sad and horrifying death of Syl’s friend and bandmate Billy Murcia. Murcia’s replacement, drummer Jerry Nolan re-ignited the band for a spell and led to the release of their self-titled debut album, but by the time of its’ follow-up, the aptly titled “Too Much Too Soon,” various members were battling various substance abuses and to make matters worse, they were still having problems breaking through to middle America.

“The Moment you hit the coastal cities you start running into a whole new demographic, one I called the Black Oak Arkansas crowd – straight ahead rockers who hated Mick Jagger because they thought he was a fag, hated David Bowie because they’d read he was a fag and they really hated us because we dressed like fags,” Sylvain writes. “Ultimately, why the Dolls were never going to make it (is that) a lot more people have closed minds than open minds, especially in America.”

By early 1975, Mercury Records dropped the Dolls and the group was back to playing small clubs, watching a new wave of bands - the Ramones, Television, Blondie precursor Elda and the Stillettos, and Patti Smith among them, learning their stage chops and gaining traction as the new hot thing. “Things were changing…management didn’t really know what to do with us, Johnny and David were running around with their own personal agendas, the animosity was growing. Then you throw the drugs in. We were going separate ways,” Syl writes.

“It didn’t matter that we were younger than a lot of these other newer outfits. We were the old-old men of the scene…that beautiful thing with which we started out had gone forever.”

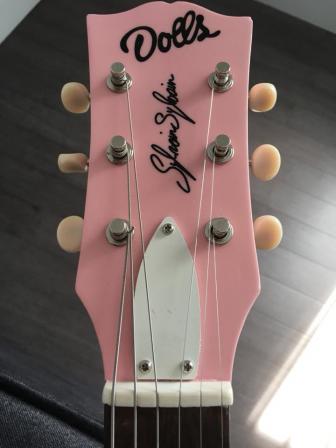

Think Pink: JT Junior guitar in Jerry Nolan Pink, which Sylvain had made last year in tribute to Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan. Hand made by Scott Sheldon California MCi custom guitar shop.

In 1975, they were temporarily propped up by Malcolm McLaren, who rented a rehearsal loft down the block from the Chelsea Hotel and had the band worked on new material, but no contracts signed, no monies were paid and no management offered. The band performed few shows – dressed in red leather and beneath a hammer-and-sickle flag - and officially dissolved while on the road in Florida. A number of new songs they’d been working on later appeared on Johansen and Sylvain’s respective solo albums as well as on recordings by Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan’s band, The Heartbreakers. That a good number of the songs stand strong as individual solo efforts provides bittersweet thoughts of what might have been.

After the band broke up, McLaren flew back to London with fashion ideas he’d picked up from Richard Hell - torn T-shirts and safety pins fixed to clothes, a flash of noise he picked up from the Dolls and organized a band with Johnny Rotten, Steve Jones, Paul Cook and Glen Matlock. They called themselves the Sex Pistols.

McLaren seemingly wanted Sylvain to come to London to be part of this new band, and a portion of the letter McLaren sent to Sylvain – which is now in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame – is reprinted in “There’s No Bones In Ice Cream.” In their communication, McLaren explains to Sylvain how he will send Syl a plane ticket to come to London, about how he’s put together Syl’s band, and something about the singer whom he calls Johnny Rotten. “He can’t sing but he’s better than Johansen,” McLaren offers.

More than 40 years later, Sylvain writes: “I’m still waiting for the plane ticket.”