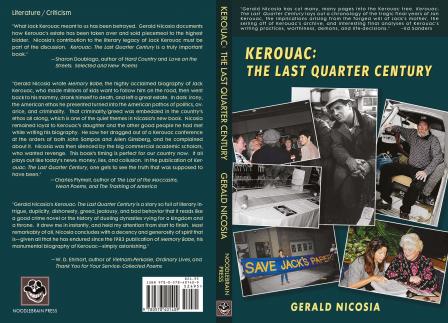

On the Road’s author Jack Kerouac died of a damaged liver, the result of longtime alcohol abuse, in St. Petersburg, Florida, on October 21st, 1969, a few months after the Tate-LaBianca slayings in Los Angeles. The two events in combination gave a public conclusion to the ceremony of countercultural wildness inspired by that book’s publication in 1957. Kerouac’s effects have been under the administrative control of his late wife Stella’s family, the Sampases, of his hometown of Lowell, Massachusetts, since his mother’s death in 1973. Jack’s mother’s will, leaving everything to Stella, was ruled a forgery in a final appellate decision. But because of a legal loophole in Florida, their control of Kerouac's estate continues. This oversight has extended to the editing and publication of posthumous Kerouac manuscripts to mixed reception. On October 21st, respected Kerouac biographer Gerald Nicosia (Memory Babe, others) published a book called Kerouac: The Last Quarter Century questioning the Sampas family’s conduct in this privileged role, considering the loss to honest academic scholarship and, most directly, the effects on Kerouac’s blood relatives, like his late daughter, Jan Kerouac, and his nephew, Paul Blake, Jr. Kerouac famously used his own life as the wrought iron from which he sculpted all his famous novels, from The Town and the City to Vanity of Duluoz, in the effort at writing “one enormous novel” about his experience this time around (he claimed, when interviewed by Ted Berrigan in 1968, to have been Wm Shakespeare reincarnate). Nicosia has written a fact-based codicil to the Duluoz Legend with his biography and other Beat books, his decades of friendship with Kerouac’s family and, most recently, in his efforts to bring Kerouac’s dark side to attention. He answered seven questions for author Zack Kopp.

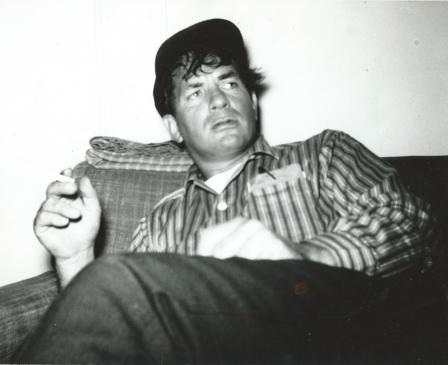

the first Grove Press edition of Gerald Nicosia’s landmark Kerouac biography Memory Babe.

Why did you write Kerouac: The Last Quarter Century? Was it an attempt to get back at the Sampas family?

GN: My main reason was to tell a part of Kerouac history that people need to know. Kerouac scholarship has been greatly skewed by the actions of the Sampas family—first, by stealing the Kerouac estate from Kerouac's own blood family with a forged will; then, by selectively releasing Jack’s unpublished archive, but only after they had edited and vetted it; and third, by only allowing scholarly work (at least on the materials they control) to be done by people who had promised and proved their loyalty to the Sampas family, and/or people who were willing to pay the exorbitant prices they usually charged for permissions. Moreover, John Sampas was a practitioner of “dirty tricks” on a scale that would have made Richard Nixon envious. My Kerouac biography Memory Babe did not go out of print because people no longer wished to read it; rather, it was forced out of print by commercial pressure placed on Viking Penguin by John Sampas’s threats to take his trade elsewhere. I should explain that once I announced my support for Jan Kerouac and her lawsuit against their family, I became Public Enemy Number One to the Sampases.

Likewise, the beneficial influence that Kerouac’s own family members could have had on Kerouac scholarship—specifically, his daughter Jan and his nephew Paul Blake, Jr.—was also hindered by Mr. Sampas’s dirty tricks. For instance, in order to gain access to royalties she already had a legal right to, John Sampas tricked Jan into signing a document that made his agent, Sterling Lord, into her agent forever. So when Jan would suggest something, such as asking that I be allowed to edit certain Kerouac reprints, Mr. Lord would simply tell her, “Sorry, Jan, that can’t be done.”

Mr. Sampas also used perks to gain a whole fleet of Kerouac scholars to back him. In many cases, all he had to do was offer some struggling scholar the right to edit an unpublished Kerouac manuscript, and he would gain an immediate diehard supporter.

The point of my book was not to “get” or “get back at” the Sampases, but to let the world know what they’ve been up to. Because all of that has a direct bearing on the future of Kerouac scholarship.

One of the things that always bothered me was something a Missouri professor named Jim Jones told me. Jones was initially a friend of mine; or, at least, he pretended to be. He wrote a few scholarly books on Kerouac. Eventually he too joined the fleet of Sampas family propagandists; he clearly saw better opportunities for his career in that direction. But at one point he made a visit to Lowell to meet John Sampas and learn the lay of the land. Later, he happened to be in California and stopped over to see me—we were still talking, because I didn’t yet know that he had decided to flip sides.

Jones said to me, “Sampas is laughing over the fact that no one will ever know all the terrible things he did to you and Jan.”

John Sampas (right), talks to Helen Kelly, program director of NYU during the Beat Generation conference in May 1994. Poet Allen Ginsberg is just behind Sampas. Sampas became executor of Kerouac’s literary properties after his sister Stella, Jack’s widow, bequeathed Kerouac’s estate to her brothers and sisters in 1990. Photo by John Paul Pirolli.

So maybe you could say the real reason I wrote this book is so that I could have the last laugh on John Sampas. Now, thanks to Kerouac: The Last Quarter Century, people do know at least some of the terrible things he did.

What's the worst example of the Sampas family’s attempts at distorting Jack Kerouac's legacy you can think of?

GN: Maybe the worst thing they did was to invert all the values that Kerouac stood for. Kerouac stood for complete openness of expression, for liberation of expression from every kind of censorship, but the Sampases have instituted a censorship based on fear that reaches into all areas of the Beat world. It's kind of like living under a police state. People are afraid to say or write the "wrong" thing--something that will displease the Sampas family--for fear that they'll be cut off from access to Kerouac materials, or worse, that outright attempts to hurt their career will be enacted against them.

I could probably go on all day if I started listing examples of this fear, but let me just mention a few. Back in the 1990's, when Jan Kerouac was still alive--but dying of kidney failure, on dialysis four times a day, and struggling to lay claim to her father's estate in court--I asked Michael McClure to speak up for her. Now Michael and I had been good friends up to that point. He used to invite me for lunch at his old Victorian on Downey Street in the Haight district, and then we'd go sit up on his roof and look out at the Golden Gate and talk about everything under the sun. His ex-wife Joanna can attest to this, if anyone doubts me. When Michael wanted someone to do an important career interview with him for the New York Quarterly, he chose me. This can also be checked out. But when I asked him to speak in Jan's behalf, he told me he couldn't do it. He told me it would hurt his career if he did. He knew the power that the Sampases wield--which is principally financial power--with Viking Penguin. Michael and I had somewhat heated words over this, since I couldn't believe he would turn his back on his good friend's daughter just for career considerations. Michael essentially cut off our friendship at that point--part of the collateral damage that the Sampases have wrought. But that's an even bigger subject, so I'll let it lie.

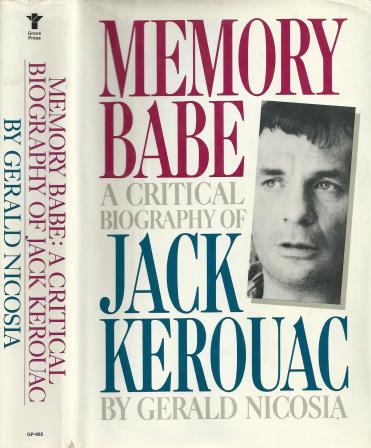

Gerald Nicosia with On the Road producer Charles Gillibert, Garden restaurant of St.-Sulpice Hotel, Montreal, July 2010. Photo by Michel Bornais.

The Sampases have proven over and over that they have no scruples about wielding their commercial power in the most brutal way. There is a terrific poet named Michael Lally, a few years older than me, who has been greatly influenced by the Beats. Back in the 1990's David Stanford, who was the Kerouac editor at Viking Penguin, began publishing a series of modern poetry books. Lally had submitted one of his books for consideration by Viking, and was told by Stanford that he would probably get a contract. Then Lally spoke up for me at a Kerouac seminar at U Mass, Lowell, in about 1999, where I was not even allowed to ask questions, and where an armed security guard kept following me around. Stanford and another Viking editor, Paul Slovak, were on that panel that I was not allowed to address--and they heard Lally make a public complaint about the way I was being treated. John Sampas was sitting in the front row, listening also. Not long afterward, Lally's poetry book was rejected by Viking.

Rather than list dozens more examples, let me just say that this climate of fear is still very much in evidence. I am planning my own "Kerouac legacy" event in Lowell during Kerouac Week this year, on Saturday October 12. I will hold it at the hall of St. Anne's Church, since I am always excluded from the "official Kerouac activities" (the notion of an official Kerouac program itself is an oxymoron) by the Sampas-sponsored-and-financed group Lowell Celebrates Kerouac. I will read from and discuss my new book there, but I am also asking noted artists and writers to say a few words about what Kerouac means to them. In addition, the musician Willie "Loco" Alexander will perform his famed song "Kerouac." I asked a long-time friend of mine, a really good scholar, who is writing a Kerouac biography, to participate in this event as one of the speakers. I will omit his name, in order to prevent retaliation against him. But he told me he would not speak at my event. He is already known as my friend, and he is terrified that the Sampases will "punish" him by refusing to give him the permissions he needs in order to publish his biography. He is terrified that his many years of work will be lost because of Sampas family spite.

As for specific examples of the damage, again, there are enough to fill a book, but let me cite one of the most egregious ones that first comes to mind. There was a couple in South Dakota named Doug and Judy Sharples, who put their whole life savings into a documentary film about Kerouac called Go Moan for Man. They began it in 1982, before any other Kerouac documentary had yet come out. They interviewed everyone; they traveled to every place Kerouac had been. The early version I saw was an incredibly well-made film. But because John Sampas had laid claim to Kerouac's image rights, as well as holding the quotation permissions, they needed to show him the film in order to get his sign-off before they could start distributing it.

John Sampas was outraged by one thing in the film: the Sharples had included an interview with me. Sampas refused to give them the permissions they needed until they removed the interview with me. The Sharples, who were people of integrity, refused to remove me from their film. They felt what I had to say was important. Their film was stymied for years, and they had to do quite a few work-arounds in order to have a legal product. In its final form, the film lacked the great potential I had originally seen in it--and as far as I know, it has never been commercially distributed.

This could have been the great Kerouac documentary we're still waiting for, but John Sampas made sure it didn't happen. His interest was not in promoting Kerouac scholarship or understanding. All he cared about was to prevent people from seeing and listening to Gerald Nicosia, because he knew the viewers would have discovered that I am not the "fraud" and "psychopath" he claimed I was.

Jan Kerouac and Gerald Nicosia, On the Road 25th anniversary conference, Naropa Institute, Boulder, Colorado, August 1, 1982. Photographer unknown.

To what degree was the recent film version of On the Road tampered with or dictated by the Sampases, and other Beat films featuring him as a character?

GN: The Sampases tamper with everything when their permissions are required; and basically, now, since they have also claimed the Kerouac image rights (which legally should have gone to Kerouac's family), it is virtually impossible to do a Kerouac-related project without their permissions. Yes, they tampered with the movie of On the Road; just look at the end of the movie, when the credits roll, and you will see this unctuous thank you in large letters to John Sampas.

I can't blame the Sampases for everything that is wrong in that movie. The French producers, a group called MK2, felt they would never get their money back unless the film showed a lot of drug use and a lot of sex (specifically, nude shots of Kristen Stewart). They thought On the Road was about promiscuous sex and illegal drug use in America. The director, Walter Salles, who respected my work, and spoke highly of Memory Babe, hired me to be a consultant to the film; and they flew me up to Montreal, in the summer of 2010, so that I could coach the actors. The first thing I told them was that fans of Kerouac do not love On the Road for the sex and the drugs; they love the novel because it is a search for identity, it talks to readers about the journey to find out who they really are. I tried to explain to them that On the Road is primarily a spiritual book. The producers did not want to hear this. They asked, "Who's going to go see a spiritual film?" So we ended up with a film filled with Benzedrine inhalers and Kristen's lovely body, and almost no one went to see it.

But the fact is, perhaps I could have had more influence on the film if John Sampas were not lobbying so hard for them to get rid of me. In the end, my name was removed from the credits, and all trace of me was removed from the lavish, full-color book that MK2 published about the making of the movie, called On the Road: Jack Kerouac the Man, the Book, the Film, the Odyssey. They went so far to erase me--I suppose for fear Sampas would rescind his permissions--that in this book, it says Kristen Stewart learned about LuAnne Henderson (the real person who was the model for the character "Marylou"), whose role she played, by listening to tapes of LuAnne made by Barry Gifford, when the fact is that the tapes of LuAnne that Kristen listened to were made by me--and Kristen herself will tell you that, if you ask her.

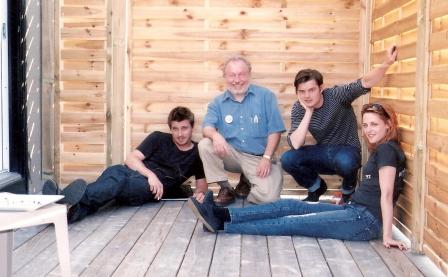

Gerald Nicosia (2nd from left) with actors he coached for Walter Salle’s movie of On the Road: from left: Garrett Hedlund, Nicosia, Sam Riley, and Kristen Stewart. At “Beat boot camp” in Montreal, July 2010. Photographer unknown.

Do you see a date in the future when the copyright to Jack's works will revert away from the Sampases in the direction of scholarship? Besides the lost manuscripts, can the damage be undone, as relates to unnecessary or ill-conceived edits and censorship of his oeuvre overall?

GN: There's not a lot of cause for optimism. Copyright, as you know, was extended with the Disney Law in the 1990's to 75 years after the creator's death.

When it was proven in court that Gabrielle Kerouac's will was a forgery, we all hoped that Kerouac's estate, including his copyrights, would go to Paul Blake, Jr., Kerouac's nephew, whom he had specifically said in a letter, the last letter he wrote, that he wanted to have his estate. But the problem was that the only will that counted was the will of Stella Sampas Kerouac, Jack's widow, leaving his (stolen) estate to her brothers and sisters in 1990. Under Florida law there is something called a "non-claim statute"--which says you only have two years to challenge the things that are left to someone in a will. It doesn't matter if what someone is leaving to someone else is stolen property. You have two years to complain, "Hey! Stella can't leave John those copyrights, because they're stolen!" After two years, John, or whoever, gets to keep whatever he has inherited. Jan didn't see her grandmother Gabrielle's will until 1994, four years after Stella had already left all those stolen materials to her brothers and sisters. So the Florida court ruled that Stella's brothers and sisters could keep what they had inherited, even though it was stolen property.

The Florida "non-claim statute" (Florida statute, Sec. 733.710, 1989) is a crazy law, since it allows people to legally pass down stolen property if no one complains within two years. A famous artistic rights lawyer in L.A., Marc Toberoff, told me he thought that law could be challenged in court. But the Blakes have no money to hire a fancy lawyer, or any lawyer, to challenge Florida law. They still haven't paid off their contingency lawyer for the will challenge, which they won but got no benefit from.

An easier fight might be for the Blakes to challenge the Sampases' claim to control of Kerouac's image. Those image rights did not pass through Stella's protected will, but are normally considered to belong to blood descendants. The Blakes, descended from Jack Kerouac's sister Caroline, are poor people living in a trailer in Arizona. They are good people, and they care about what happens to Jack Kerouac's legacy. I believe they would handle those image rights more responsibly than the Sampases have.

Jack Kerouac created at least nine roll manuscripts. He even retyped the notebooks for Mexico City Blues on a roll of teletype paper. Those rolls are the most important part of his archive, but not one of them is currently in a library. They were all sold into private hands by the Sampases. I don't see how we can ever put that part of Kerouac's archive back together. But the more that we can help to empower the Blakes, the more reconstruction we can hope for.

The other thing is to bring public pressure on the Sampas family to permit exact versions of Jack Kerouac's work to be published, unbowdlerized and uncensored, and to hire knowledgeable editors who have universal respect as Kerouac scholars--not just handpicked yes-men and -women--to edit these works with the care and expertise they deserve. But we need to make our voices loudly heard, and so-called respectable scholars have to stop giving in to Sampas-family demands just so that they can get a leg up on the competition.

Gerald Nicosia and Kristen Stewart at the after-party for On the Road after it was shown at the Cannes Film Festival, May 23, 2012. Photo by Noémie Sornet.

You have talked about the Sampases removing a lot of Jack Kerouac's "dark side" from his works? In your opinion, what was Kerouac’s dark side?

GN: Jack Kerouac was a deeply tormented person. He used alcohol--vast amounts of it, a quart of whiskey and two dozen beers a day the last few years of his life--to quell his depression, but also, as he admitted, as a "slow form of suicide," since he believed as a Roman Catholic that to kill himself with any of the usual quick methods would be a mortal sin.

Almost everything that came out of that torment and depression can be cited as part of Kerouac's dark side: his misogyny, anti-Semitism, alcoholism, confused sexuality, paranoia, abusive behavior, the disowning of his own daughter, his extreme miserliness with money, and so on. The Sampases have tried to hide a lot of this because they see Kerouac as a product, like the latest model car they have been given to market, so they want to highlight its shiny parts and hide the broken parts that might scare away buyers. Of course they also have a practical, mercenary reason for wanting people to forget that Jack had a daughter, or to believe that daughter wasn't really his daughter at all--since they robbed her of his estate.

Lately a lot of work has been done in exploring the origins of depression, especially suicidal depression, in the occurrence of an overwhelming loss in early childhood. In Jack Kerouac's case, he lost his older brother Gerard, the saintly Gerard, when Jack was only four years old. Supposedly people that sustain that sort of large loss in early childhood become self-aggrandizing and suicidal at the same time--a pattern which seems to fit Kerouac well. I think future Kerouac studies need to explore that more. But first Kerouac's dark side has to be fully revealed, before we can meaningfully explore it.

What role would you say Jack’s friendship with Sebastian Sampas (Sabby Savakis) played in his life after leaving his hometown?

GN: Sammy, as he was called, did not see a lot of Jack after they left Lowell, and then in 1944 he died in Italy. Jack and Sammy hung out a little in New York and saw Saroyan plays, and Sammy visited Jack, worried, when Jack got himself thrown out of the Navy by running naked across the Newport drill field yelling, "Geronimo!" Sammy had given Jack the courage to be a poet in that rough workingclass milltown of Lowell, where poets were considered "fags," and both looked down on as less than men. He was also Jack's greatest champion, believing in Jack's talent (as no one other than Jack did) and even writing Saroyan a letter pleading with him to help Jack in his literary career. In many ways, Sammy seems more in touch with his feelings than Jack was, and Jack was clearly unnerved by Sammy's expressing how much he loved Jack. People have speculated, if Sammy had lived, would he have brought Jack out of the closet? But Jack's sexuality was too conflicted to even have a closet to come out of. He was not gay, as Ellis Amburn tried to make him out; and Sammy clearly was gay. I don't think there would have been any happy ride for them into the sunset in a wedding carriage, had Sammy lived. But the one main thing Sammy gave him was the courage to be himself, to express his inmost self to the world without fear. As a side note, and I've always wondered about this, Bernice Lemire, a fellow French-Canadian from Lowell, who wrote Kerouac's first biography as a doctoral thesis, told me she found out the dark secret that Sammy had not died on Anzio beachhead in Italy but had committed suicide later in the Army hospital. It may be that Sammy's own torment was somewhere near the level of Jack's, which would explain even more their bonding.

What is the Sampases' legitimate role? Do they have a right to control the town festival known as Lowell Celebrates Kerouac? Do they have a right to oversee the editing of posthumously-published Kerouac books, or even to control other writers quoting him?

GN: The problem is that Lowell Celebrates Kerouac masks as a town festival, but there is Kerouac politicking going on throughout it. There is a conscious effort to keep out even the mention of Kerouac's real family, and there is a constant reinforcement of the supposed benevolence and virtue of the Sampas family. My own sense is that it misses the mark by quite a stretch when it comes to Kerouac, and so misleads a lot of people who come to Lowell every year for the festival, hoping to learn more about Kerouac and the sources of his art. They sell Kerouac bacon cheeseburgers with Jack Daniels sauce (which strikes me as in bad taste, since Jack Daniels was one of the drinks that helped kill him), and show people some of the sites where he lived and hung out--and there's an ungodly amount of drinking, which is not one of Kerouac's better legacies. I would like to see a more academic-focused get-together every year, but knowing how much smalltown politics goes on in Lowell, I'm not sure an unbiased Kerouac symposium could be put on there. It would probably be impossible to keep the Sampases out of the celebration, but I think it would be better off without them. They are the family that stole Kerouac's estate, after all. It seems the height of irony to have them controlling this remembrance of him year after year. All the more should they not be controlling how his posthumous books are published, or who writes about him, or who can quote him. But I don't know how we change that short of a legal challenge to the Florida non-claim statute.

Jack Kerouac’s nephew Paul Blake, Jr., living in his broken pickup truck in a Sacramento junkyard, October, 2001. Photo by Gerald Nicosia.

Has John Sampas or anyone else representing the Sampas family made a public statement with regard to these allegations, or have they elected to remain silent?

GN: They try to act like the Florida trial of the will on April 1, 2009, was a sham. It wasn't at all, and it was presided over by one of the toughest judges in Florida, George Greer, the judge who oversaw the rough-and-tumble Terri Schiavo right-to-die legal case. The Sampases elected to remove themselves from the trial, using the non-claim statute so that they would have no liability. Because there needs to be two sides in any adversarial action, the judge appointed an administrator ad litem to argue for the validity of the will, Elaine McGinnis, and she did as good a job as she could. But after Greer issued a very strongly-worded opinion, asserting that there was no shade of doubt that the will was a forgery, the Sampases then said, "If we had mounted our own defense, we could easily have proved the will genuine." Which really begs the question, if they could have won so easily, why did they bail out of the case with the non-claim statute?

Jack’s descendants were reduced to the beat-est of circumstances—in part, by consequence of the Florida “non-claim statute.” This paints a very Kerouacian (Dostoevskyan?) picture of the Sampas family’s significance, being at once the source of his first best friend and oppressor of his own progeny. How does it feel to be writing a postscript to the Duluoz Legend, but constrained by legalities?

GN: A number of people have compared Kerouac: The Last Quarter Century to a novel. I have to admit, I didn't originally see it that way. But there are some powerful themes in it that suggest fiction, such as Kerouac's own screw-ups being passed down to his family--and the way that genius is picked apart for money and power in this country. Luckily I was not as constrained by legalities as I might have been, had the will not actually gone to trial. The legal verdict of forgery, which was upheld on appeal, made it possible for me to say a lot of things I otherwise might have had to tiptoe around.

I guess in some sense, my book does show the dark path that the Duluoz Legend, and Kerouac's own life, was actually heading down. It's a postscript Kerouac himself could have foreseen, had he been honest with himself, but whenever he'd start to glimpse the truth, he'd just imbibe more booze to shoo it away.

By the same token, it's sad that the Sampas family can't see the good possibilities here, the possibilities you are suggesting when you bring up the bookend influences their family had on Kerouac's legacy. They could turn things around, and prove themselves once more a blessing for Kerouac and his family--if, for instance, they would help the Blakes out financially, and share control of Kerouac's work with his own blood family. They've already banked millions off Kerouac. What would it cost them to step aside now, to say, We've had our turn, we're lucky for it, but we're now handing the reins over to the people who should truly have held them? The Sampases would gain nothing but honor by doing that. But their drive for profit seems to preclude that. Profit seems to have them focused on only one thing.

The roll manuscript of Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road, on display at Christie’s in downtown San Francisco, May, 2001, in an effort to increase buyer interest. Photo by Gerald Nicosia.